The mushrooming growth of tuition centres across the length and breadth of the country is a manifestation of the collapse of the public school system in PakistanIT’s fairly well-known that the system of education that has evolved in Pakistan over all these years is unmatched in several respects. Firstly, it is composed of contradictory elements. The conceptual elements in the education of Pakistan that contradict one another are instrumental in perpetuating the socio-political and economic structures of the state. The public education system caters to almost 60 per cent of all enrolled students in Pakistan. Private English medium schools entertain the middle and lower middle classes in cities and villages while so-called elite schools provide education to a tiny minority in this country. Moreover, except the works by a few individuals, the existing literature on the education system intentionally or unintentionally perpetuates the theory and practice of education thus helps maintain the existing configuration of power in state and society.

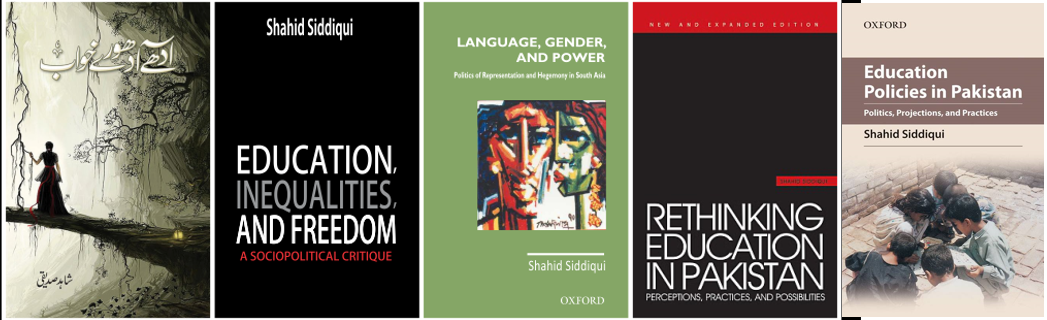

The book under review by Dr Shahid Siddiqui is an example of reflections on the fundamental issues of public education in Pakistan. The writer has been successful in debunking myths surrounding the theory and practice of public education in this country, and in providing alternatives to establish a vibrant system based on the progressive theory of education.The author has dealt with the themes of policy issue, teacher and teacher education, curriculum and materials, language issues, research and assessment while constructing a frank and informal discourse.The book is probably the first effort of its kind to bring deeper academic issues to the domain of general discourse. The writer has tried to form an argument in support of making education an agent of social and economic change in society. For example, in the chapter on financing education the author has argued that it is the lack of political will to devise policies and the lack of competence in bureaucracy to implement those policies so as to prevent education from becoming a vehicle for any meaningful change in the society.

Faculty development is undoubtedly a springboard for providing opportunity to individuals to develop pedagogical grip on the vital issues both inside and outside the classroom. The author advocates self-reflection as matter of approach in teacher training institutes to set the stage for an attitudinal change. The role of a teacher, the author argues, has to be redefined. Knowledge is not to be transmitted but constructed, negotiated and reconstructed. The teacher has to perform the role of a guide, facilitator, researcher, organiser and an agent of social change. The complex issue of socio-cultural and politico-economic influence on an individual and its relationship with human agency needs a little more deliberation nonetheless. Can an individual teacher bring about change in the collective social behavioural system?The author has taken up another intricate issue, that of language and language teaching in Pakistan after convincingly summarising the debate going on around the globe on this matter of vital importance. (Though one would have liked to read about the threats to the diversity of the world, especially to the bio-linguistic diversity in the context of globalisation of a few European languages.) Thousands of languages are said to have been faced with threat to their survival that may lead to homogenisation of cultures around the globe. Significant questions in this regard are: how can English language skills be developed in a bilingual and multilingual context? How can language education be linked to critical thinking through critical listening, reading and writing? The writer’s discussion on linking literature with language in the ELT classrooms in Pakistan speaks of his in-depth insight into the ELT scenario in Pakistan.On of the most interesting sections of the book is a thought-provoking discussion on research paradigms. The discussion falls just short in addressing the issue of link between research paradigms and configuration of power in the society. The politico-economic relations within a social structure have close links with the generation of new knowledge and the construction of a reality. If a reality is perceived to be absolute and unchangeable, it is likely to be measured with quantitative research tools with varying degrees of certainty. This is in tandem with the structural, formal and constructionist view of society. The flux and reconstitution of reality stays out of the discourse. If it is assumed that a reality has multiple dimensions and is always in a flux, it is then likely to be understood through qualitative tools. A reality in this paradigm can be changed and reconstructed. As events, phenomena and procedures are usually based on a certain concept of reality; they are liable to continuously change and fluctuate. This paradigm seems to be in tandem with the post-structuralist and post-modern concept of social structure.Some interesting phenomena of the education system in Pakistan have been candidly discussed in the book. One such interesting phenomenon is the workshop syndrome in faculty development programmes in Pakistan that defeats the very purpose of its existence in the first place. The discussion on ‘touch-and-go’ teaching, currently popular among university faculty in Pakistan, is witness to the author’s incisive observation. The mushrooming growth of tuition centres across the length and breadth of the country is a manifestation of the collapse of public school system in Pakistan, the author argues, but these tuition centres are emerging as a parallel institution in themselves. The author has tried to put the issue in context.Another significant area in the education system is curriculum development. The issue has been hotly debated by educational theorists in recent times. The issue of curriculum development is also one of the most controversial areas of educational theory in Pakistan. Dr Siddiqui has raised some very important questions while discussing the role of teacher in curriculum development and implementation emphasising the role of interaction between teacher, students, materials and school milieu. Do we have proper teacher’s education programmes which focus on developing reflective practitioners? Do we have an appropriate system of monitoring? Are we satisfied with the process of evaluation of curriculum? And finally, are we considering teacher’s role central to curriculum construction?

By Shahid SiddiquiParamount Publishing Enterprise

Available with Paramount Books, Karachi

ISBN 0-494-494-490-6196pp. Rs345

I Really appreciate your blog nice work thanks for sharing info... Teacher Training Pakistan

ReplyDelete